|

Zippo, The Windproof Lighter

Zippo Manufacturing Company is world famous for its

Zippo windproof lighter, its lifetime guarantee, and the distinctive

"click" it makes when opened. Zippo Manufacturing Company is world famous for its

Zippo windproof lighter, its lifetime guarantee, and the distinctive

"click" it makes when opened.

Zippo originated in a small Pennsylvania town at a

time when the United States was in its worst depression in history.

Zippo's success came about through imagination and hard work and the

creation of a durable and functional product along with creative

marketing and attentive service.

It all started on a summer evening in 1932, at a

dinner dance held at the Bradford Country Club in Bradford,

Pennsylvania. Attending the dance was George G. Blaisdell. It is rumored

that Blaisdell and a friend stepped out on the terrace of the Pennhill

Country Club and there, he saw the friend trying to light up a

cigarette. The ugly lighter he was using was totally out of place in the

hand of his perfectly attired friend. It took two hands to operate the

lighter. The sight of his friend trying clumsily to open the lighter's

lid was so comical that Blaisdell almost started to laugh. "You're

all dressed up. Why don't you get a lighter that looks decent?"

blurted Blaisdell. His friend replied, "Well, George, it

works!"

Impressed with the fact that it worked, Blaisdell

decided to try to sell the lighters himself. He obtained rights to

distribute the product in the United States, imported them from Austria

for 12 cents each, and attempted to sell them for $1 each. This venture

failed, mainly because of the clumsy nature of the lighter's design.

Blaisdell then decided to design his own lighter, one that was

attractive, easy to use, and dependable.

The first thing Blaisdell did was to make the lighter

smaller to be able to fit in the palm of the hand, and he incorporated a

hinge to hold the lid to the bottom, making it an integral part of the

lighter. This enabled the user to open the lighter using only one hand.

He kept the chimney design which protected the flame under adverse

conditions. The result was a lighter that looked good and was easy to

operate. Blaisdell liked the name of another recent invention, the

zipper, so he christened his lighter the "Zippo" and his new

firm, Zippo Manufacturing Company.

Production of Zippos began in 1933 in a $10 per month

rented room over the Rickerson & Pryde garage in Bradford. The shop

had $260 in equipment and two employees, from which came lighters

retailing for $1.95. The first Zippo lighter is currently displayed at

the Zippo/Case Museum in Bradford.

In the company's ledger at the end of the first

month, 82 units were produced and sales were $69.15. To market the new

product, Blaisdell came up with the practice of a lifetime warranty, a

concept that began with the first Zippo lighter and has remained the

same to the present day. The repair and sale of parts after the

expiration of the warranty was a major source of the business revenue. In the company's ledger at the end of the first

month, 82 units were produced and sales were $69.15. To market the new

product, Blaisdell came up with the practice of a lifetime warranty, a

concept that began with the first Zippo lighter and has remained the

same to the present day. The repair and sale of parts after the

expiration of the warranty was a major source of the business revenue.

Zippo repaired all types of defects without charging

a cent. The lighter was returned postpaid within 48 hours with a note

reading, "We thank you for the opportunity of serving your

lighter". The concept of a lifetime warranty became Zippo's primary

marketing scheme.

Sales of the lighters got off to a slow start, with

only 1,100 sold during the first production year. Blaisdell tried all

kinds of methods to move his brainchild. He gave away samples and gifts

to long-distance bus drivers, jewelers, and tobacconists. In December

1937 he paid $3,000 of mostly borrowed money for a full-page ad in

Esquire magazine after he found that retailers shied away from products

that were not advertised. Unfortunately, Blaisdell did not yet have

sufficient distribution to take advantage of the effect of such

advertising so this gamble failed to pay off.

While handling sales himself and struggling to

develop a market for his windproof lighter, Blaisdell also tinkered with

the design. The lighter was shortened by a quarter inch in 1933,

decorative diagonal lines were added in 1934, the hinge was placed on

the inside of the case in 1936, and rounded tops and bottoms replaced

the square corners of the original design in 1937. This last alteration

was important from a production standpoint as the lid and bottom could

now be formed as a whole, eliminating the soldering process.

Blaisdell achieved his first big sales break in 1934

when he started selling Zippos on punchboards, two-cents-per-play

gambling games popular in U.S. tobacco and confectionery shops,

poolrooms, and cigar stands. Before punchboards were outlawed in 1940,

more than 300,000 Zippos were sold through this game of chance, enough

for Zippo Manufacturing to achieve its first profits.

While punchboards were a short-lived chapter in Zippo

history, another of Blaisdell's marketing methods had a much

longer-lasting impact. In 1936 an Iowa life insurance company ordered

200 engraved lighters that it gave to its agents as contest prizes.

Bradford's own Kendall Oil Company ordered 500 engraved lighters for its

customers and employees. Thus began Zippo's specialty advertising

business, which would become an increasingly important venture in the

coming decades.

This was the beginning of the specialty advertising

business for the Zippo. Zippo Manufacturing Company discovered the

market potential of the product as an adverting medium. Soon, Zippo

produced a pamphlet aimed at corporations to use Zippo as a pocket

salesman. Designs such as the military, airplanes, tourists spots,

sports teams, comic characters and universities also appeared on Zippo's

lighters. Corporate novelty and commemorative lighters were produced

only in limited numbers. In essence, the Zippo lighters were the

salesman in a pocket.

In 1936 Zippo began to engrave initials and providing

two types of metal insignia on the lighter, the "Scotty

Group", depicting dogs, and the "Drunk", portraying a

drunkard leaning on a gaslight pole. The engraving of the initials cost

the owner of the lighter one dollar, or 75 cents for an insignia. The

return shipment was paid by the owner, C.O.D. The initials were engraved

in a frame against a background color. The various colors include, red,

green, blue, yellow, orange, purple, and white. During the thirties and

forties, initialed gifts were very popular. It gave the consumer the

sense of individuality. In 1936 Zippo began to engrave initials and providing

two types of metal insignia on the lighter, the "Scotty

Group", depicting dogs, and the "Drunk", portraying a

drunkard leaning on a gaslight pole. The engraving of the initials cost

the owner of the lighter one dollar, or 75 cents for an insignia. The

return shipment was paid by the owner, C.O.D. The initials were engraved

in a frame against a background color. The various colors include, red,

green, blue, yellow, orange, purple, and white. During the thirties and

forties, initialed gifts were very popular. It gave the consumer the

sense of individuality.

In 1936, Zippo appeared on a mail-order catalog. It

was a wholesale catalog of a company in Minnesota directed to retail

stores. The retail price was $2.00, which increased slightly from the

price first sold. Blaisdell also visited many retail stores all over the

country to make business relations.

The sports related designs began to appear on the

Zippo lighters in 1937. The first sports model was the 275, which was

sold for $2.75. The 275 models with a carrying strap also appeared in

the Sports Series. Earlier sports models included the Golfer, the

Fisherman, the Bulldog, the Hunter, the Greyhound, and the Elephant. In

1938, the Scotch Terrier, the Fisherman and the Bulldog were the only

models on the Sports Series.

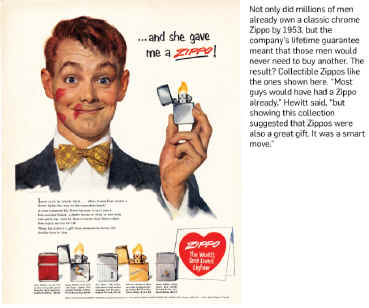

In 1937, Zippo ran a one-page advertisement in the

December issue of Esquire, aimed at the Christmas shoppers. The ad had

an illustration of a woman, "Windproof Beauty", drawn by Enoc

Boles, lighting up a cigarette in the wind. It was a different image

from the previous image, which emphasized outdoor sports. Using an

illustration of an attractive woman, the advertisers were aiming to

appeal directly to the readers of the magazine, which was targeted at

the urban male. The Windproof Beauty illustration was also used for

packaging and became one of Zippo's characteristic images. This was a

memorable advertisement for Zippo, the company would later run regular

advertisements in many major magazines such as Life, the Saturday

Evening Post, and Reader's Digest.

With sales increasing thanks to the punchboards and

the special markets deals, Blaisdell expanded his operations. First, the

production facility expanded into the entire second floor of the

Rickerson & Pryde building. In 1938 the factory and offices were

both moved into a former garage on Barbour Street in Bradford. That same

year, Zippo's first table lighter debuted, a four-and-a-half inch tall

model that held four times the fuel of a pocket lighter. Production of

the table lighter stopped in Oct 1941, but was made available again in

1947. In 1939 Zippo introduced a sophisticated new lighter model, the

14-karat solid gold Zippo, available in both plain and engine-turned

models. With sales increasing thanks to the punchboards and

the special markets deals, Blaisdell expanded his operations. First, the

production facility expanded into the entire second floor of the

Rickerson & Pryde building. In 1938 the factory and offices were

both moved into a former garage on Barbour Street in Bradford. That same

year, Zippo's first table lighter debuted, a four-and-a-half inch tall

model that held four times the fuel of a pocket lighter. Production of

the table lighter stopped in Oct 1941, but was made available again in

1947. In 1939 Zippo introduced a sophisticated new lighter model, the

14-karat solid gold Zippo, available in both plain and engine-turned

models.

With the onset of U.S. involvement in World War II,

the U.S. government forced the halt in production of many consumer

products. Blaisdell continued Zippo production, but as he had during

World War I, he again moved into government contracting, all Zippos

became destined for the U.S. military. With brass reserved for military

uses only, the wartime lighters were made of a low-grade steel. Since

this provided a poor finish, they were spray-painted black then baked,

which produced a crackle finish. The black, rough-surfaced Zippo is the

authentic World War II Zippo. The advantage of the black finish was that

it did not reflect light that would attract enemy attention on the

battlefield.

Blaisdell sold some of these Zippos to the military

post exchanges at such a low price that they were then resold for $1.00,

making them the most affordable lighter available. He also sent hundreds

of lighters to celebrities, including the famous war correspondent Ernie

Pyle who then gave them away to servicemen overseas. Pyle gave Blaisdell

the nickname "Mr. Zippo." Through these actions, the Zippo

became the favorite lighter of GIs, whose loyalty to the product would

help fuel postwar sales. Numerous war stories also helped cement the

Zippo as an American icon, the Zippo that stopped a bullet, that cooked

soup in helmets, that illuminated the darkened instrument panel of an

Army pilot's disabled plane, enabling him to land safely.

Zippo's rise to prominence during World War II is

reflected by the large number of films that featured Zippo lighters,

both those made during that period and afterward. Whether it's Donna

Reed lighting Montgomery Clift's cigarette in From Here to Eternity

or Errol Flynn wielding his Zippo in Objective Burma, a Zippo

lighter provided an instant air of authenticity. Director George Stevens

was captured using his Zippo during the making of his documentary D-Day

to Berlin. In 1945, Vincent Minelli's, The Clock, used a

lighter to bring Judy Garland and Robert Walker together for a whirlwind

courtship. The dialogue indicates that it is a Zippo lighter, but the

shortage of civilian Zippo lighters forced the use of a stand-in. Zippo's rise to prominence during World War II is

reflected by the large number of films that featured Zippo lighters,

both those made during that period and afterward. Whether it's Donna

Reed lighting Montgomery Clift's cigarette in From Here to Eternity

or Errol Flynn wielding his Zippo in Objective Burma, a Zippo

lighter provided an instant air of authenticity. Director George Stevens

was captured using his Zippo during the making of his documentary D-Day

to Berlin. In 1945, Vincent Minelli's, The Clock, used a

lighter to bring Judy Garland and Robert Walker together for a whirlwind

courtship. The dialogue indicates that it is a Zippo lighter, but the

shortage of civilian Zippo lighters forced the use of a stand-in.

The military connection extends through films about

the Korean War and Vietnam. A Zippo linked Karl Malden and Richard

Widmark in Sergeant Terror, while Gregory Peck counted on his

Zippo for moral support in Pork Chop Hill. The Green Berets,

starring John Wayne, was extremely popular. Apocalypse Now

director Francis Ford Coppola set the haunting tone of his film in the

opening scenes with Martin Sheen's Colt revolver and a Zippo lighter.

Meanwhile, wartime production peaked in 1945 when three million Zippos

were made.

The Zippo repair clinic became famous in its own

right by backing up the Zippo guarantee. Repaired lighters were returned

at no cost to the customer, not even return postage. The clinic provided

more than just customer goodwill. It also provided invaluable

information about design flaws. Over the long run, the repair clinic

found that a faulty or broken hinge was the most common reason for a

Zippo to be returned. But soon after World War II, in 1946, Blaisdell

discovered that the most frequent repairs were for worn striking wheels,

wheels that had been coming from an outside supplier. Blaisdell

immediately stopped production to address the problem. He decided to

bring production of the wheels in-house and spent $300,000 on a new

flint wheel capable of firing a lighter as many as 78,000 times. This

top-quality wheel was produced by a knurling operation that remained a

company secret.

At the end of the war in 1945, Zippo hit the road

selling lighters to peacetime America. A promoter at heart, Blaisdell

envisioned a car that looked like a Zippo lighter. He hired Gardner

Display of Pittsburgh to design the vehicle, a 1947 Chrysler Saratoga

with larger-than-life lighters stretching above the roof line, complete

with removable neon flames. The lids of the lighters snapped shut for

travel. The word Zippo was painted on the side in 24-karat gold. The

Zippo Car was a hit, heading up parades and special events.

In the two years after its creation, the Zippo Car

traveled to all 48 continental U.S. states and participated in every

major parade in the nation but the remarkable car had some problems. The

weight of the giant lighters put enormous pressure on the tires, which

blew out easily. The armor-plated fenders made the car impossible to

jack up for a tire change.

In the early 1950s, Blaisdell asked that the car be

returned to Bradford for an overhaul. Instead, the car was taken to a

Pittsburgh Ford dealer for renovation, which would have proven too

costly. Blaisdell’s enthusiasm for the car fizzled out and the car was

pretty much forgotten about. Several years later when Zippo looked into

the whereabouts of the car, it couldn’t be found. In the early 1950s, Blaisdell asked that the car be

returned to Bradford for an overhaul. Instead, the car was taken to a

Pittsburgh Ford dealer for renovation, which would have proven too

costly. Blaisdell’s enthusiasm for the car fizzled out and the car was

pretty much forgotten about. Several years later when Zippo looked into

the whereabouts of the car, it couldn’t be found.

In 1996, Zippo purchased another 1947 Chrysler New

Yorker Saratoga and started over again, making the car lighter with a

sturdier suspension. The new Zippo Car is just as popular as its

predecessor, making rounds across America, now in a truck instead of

being driven across the nation. When not on the road, the Zippo Car

makes its home at the Zippo/Case Museum in Bradford, Pennsylvania.

Starting in the mid-50s, date codes were stamped on

the bottom of every Zippo lighter. The original purpose was for quality

control, but the codes have since become an invaluable tool for

collectors.

The launch of the Slim model in 1956 was a major

milestone. This version was designed to appeal primarily to women. The

first non-lighter product was a steel pocket tape measure, or

"rule" as it was called, introduced in 1962. Other items have

been added and deleted from the Zippo line since the 1960s. Many were

primarily geared to the promotional products division. The roster

includes key chains, pocket knives, golf greenskeepers, pen-and-pencil

sets and the ZipLight pocket flashlight.

On the music scene, Zippo lighters have been raised

high since the 1960s as a salute to favorite performers, a gesture later

dubbed the "Zippo Moment". The famous Zippo "click"

sound has been sampled on songs, and the lighters themselves have been

featured on album covers, tattooed on rockers’ skin, and wielded in

Rolling Stone photo shoots.

The Vietnam War represented something different from

all other American Wars, previous and since. There were the regular army

soldiers, many raised by World War II heroes and viewing their job as a

duty and privilege. There were victims of fate, the unwilling, drafted

by lottery, many poor and minority, resentful of their government and

military superiors. And there were those along for the ride, not

interested in glory or politics, merely trying to follow orders and earn

their ticket home. Regardless, they were all connected by the Zippo, the

functional tool carried by nearly all soldiers since World War II.

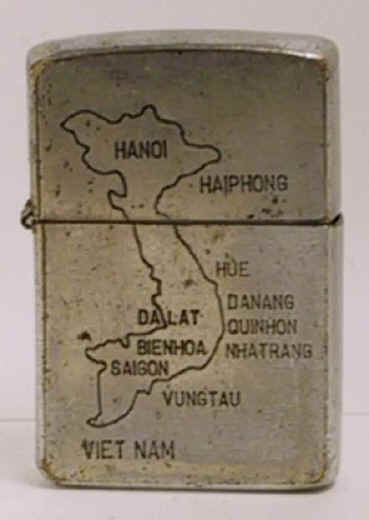

During the Vietnam War, several items became the

canvasses on which soldiers painted their feelings. The Zippo was one of

these items. According to collectors, 200,000 Zippos were used by

American soldiers in Vietnam. Zippo merchandise quickly found its way

onto the black market. Soldiers were able to buy brand new Zippos

without having to go to the PX store. Vietnamese craftsmen would engrave

anything from pictures to phrases onto the Zippo for the soldiers. The

most popular motif engraved on soldiers' Zippo was the map of Vietnam.

Every soldier had his own personalized Zippo, which accompanied him

until the fall of Saigon.

The Zippo played a part in almost every daily

activity of a soldier. The shiny top provided a handy mirror and the

lighter's flame warmed the stew at mealtime. Soldiers kept salt in the

bottom cavities, called canned bottoms, of their Zippos, to replenish

lost body salt. Other legendary Zippos were used to transmit signals or

even provided a shield against enemy bullets. Staff Sergeant Naugle, who

was saved because he was able to signal his position to the rescue

helicopter, had a Zippo in his hand. Among men that had a close call

with death, one of the luckiest was Sergeant Martinez, who kept a Zippo

in his chest pocket. A bullet struck his chest, only to be stopped by

the Zippo. This was reported in Life magazine and also appeared in

various advertisements regardless if it was factual or not.

Zippos were also used in military operations in which

troopers would spray gasoline over the area to burn enemy compounds and

dwellings. Zippos were used so frequently in Search & Destroy

missions that GIs nicknamed them "Zippo Missions" or

"Zippo Raids."

Zippo lighters used by American soldiers during the

Vietnam War have become collector's items. Every Zippo from the war

conveys a great sense of having been there on the battlefield. The

soldiers who faced death and stood on the brink of hell, carrying their

Zippos, transformed these simple lighters into an essential part of

their own bodies and souls. Zippo lighters have since become priceless

collector's items.

In 1982, Zippo celebrated the 50th anniversary of its

lighters, by producing a replica of an early model for the first time.

It was a flat bottomed, solid-brass model and had a diagonally-cut line

on both the top of the lid and the bottom of the case. This was the

reproduction of the 1937 model and came in a box that had the same

design as the one used between 1935 and 1940, which bore the

illustration of the "Windproof Beauty". The Commemorative box

had a gold finish rather than the silver finish from the original. This

reproduction was based on the 1935 prototype box that was not used for

production. The original 1932 Zippos are now very rare.

Zippo’s diverse product line continues to grow, and

now includes lighter accessories; butane candle lighters; watches, men's

and women's fragrance, and lifestyle accessories for men; and the

developing line of heat and flame products for outdoor enthusiasts.

Zippo also owns the Ronson brand of lighters and fuel.

In 2012, during its 80th anniversary year, Zippo

production surpassed the milestone of 500 million lighters since Mr.

Blaisdell crafted the first lighter in early 1933. The lighter is

ingrained in the fabric of both American and global culture.

Today, though most products are simply disposable or

available with limited warranties, the Zippo lighter is still backed by

its famous lifetime guarantee, "It works or we fix it free.™"

In more than 80 years, no one has ever spent a cent on the mechanical

repair of a Zippo lighter regardless of the lighter’s age or

condition. It’s estimated that there are some four million Zippo

collectors in the United States and millions more around the world.

Mr. Blaisdell passed away on October 3, 1978. After

his passing, his daughters inherited the business. Today, George B.

Duke, Mr. Blaisdell’s grandson is the sole owner and Chairman of the

Board. Gregory W. Booth is President and CEO.

The Zippo/Case Museum opened in July 1997. It is

located in Bradford, Pennsylvania at 1932 Zippo Drive. The

15,000-square-foot facility includes a store, museum, and the famous

Zippo Repair Clinic, where the Zippo lighter repair process is on

display. |